See photos from Steamtown’s Collection of DL&W photos of the bridge’s construction.

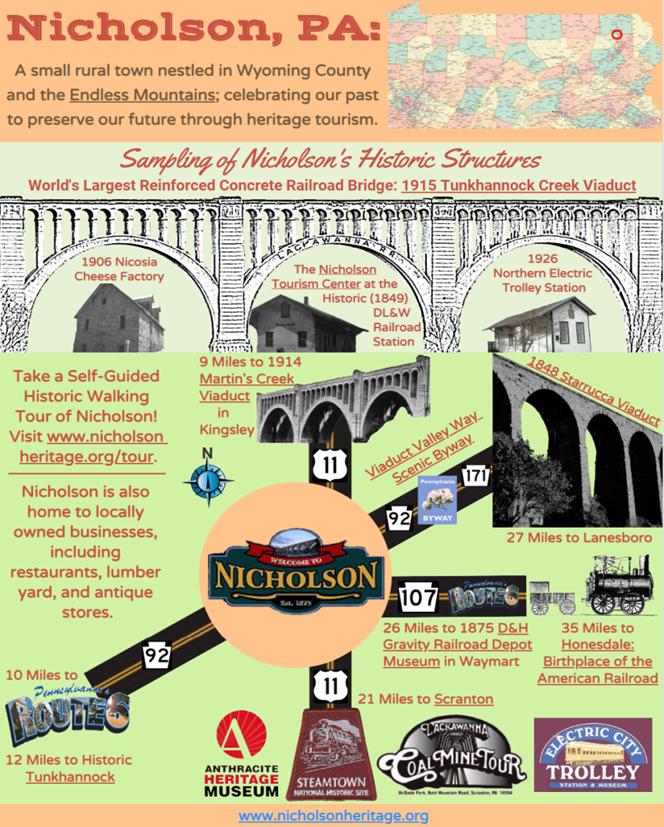

The Tunkhannock Creek Viaduct, also known as the Tunkhannock Viaduct or the Nicholson Bridge, was built by the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W) in 1912 and was completed, dedicated and ready for use on November 6, 1915. This massive reinforced concrete bridge celebrated its centennial in November 2015! The Tunkhannock Viaduct received its proper name from the Tunkhannock Creek that it traverses. However, it is also known as the Nicholson Bridge because of the small Pennsylvania borough where it is located.

This engineering marvel was designed by Abraham Burton Cohen with George G. Ray as the chief engineer of the project. Concrete was first poured in January 1913 with the entire project using 185,000 barrels, or 1,093 carloads, of cement producing 167,000 cubic yards of concrete. In addition, about 1,140 tons of steel were used to reinforce the concrete. Moreover, the bridge was built to endure 6,000 pounds per square foot, considering that some engines at that time would weigh 233 tons. At that time, the bridge itself cost $1.4 million to build.

Five hundred men of which only half or less were skilled laborers worked 24 hours a day with very little equipment. All they had were steam shovels, dynamite for excavation and a cement mixer that was built on-site. At piers 5 and 6, the workers encountered quicksand making it necessary to use pneumatic chambers and many extra hours of manpower. The DL&W would not allow dynamite to be transported on their railroads so the dynamite was shipped by the Lehigh Railroad into Springville and transported to Nicholson by horse and wagon.

The Nicholson Bridge is 2,375 feet long and 34 feet wide. It is 240 feet above stream level and 300 feet above bedrock. There are twelve arches with ten being 180 feet across and two being 100 foot arches, one at each end of the bridge that are totally buried in the land fill. In Theodore Dreiser’s 1916 travel biography, he called the bridge: “A thing colossal and impressive. Those arches! How really beautiful they were. How symmetrically planned! And the smaller arches above, how delicate and lightsomely graceful! It is odd to stand in the presence of so great a thing in the making and realize that you are looking at one of the true wonders of the world.” Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and former President Theodore Roosevelt were among the many people that came to view this one of a kind bridge.

This remarkable construction and engineering feat of its time was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (#77001203) on April 11, 1977 due to its national architectural, engineering and transportation significance. The nomination application that was submitted in August 1976 affirms the national significance of the viaduct: “The literal keystone in the early-twentieth-century modernization of a major railroad, Tunkhannock was put up at a time when a reinforced-concrete structure of such a size was considered venturesome, and before perfection of a number of now commonly accepted techniques in concrete construction.” The national significance narrative was taken from William S. Young’s 1967 book: The Great White Bridge (pp 19-20).

Earlier in 1975, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) designated the bridge as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark due to its significant contribution to the development of the United States and to the profession of civil engineering. As of 2008, only 244 landmarks in the world received this designation. From the ASCE

website: “The Tunkhannock Viaduct represents a great feat of construction skill and a successful departure from contemporary, conventional concepts of railroad location in that its main line traversed the regional drainage pattern, therefore reducing the distance and grade impediments to economy of operation.”

Additionally, the viaduct has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), which was established in 1969 by an agreement by the National Park Service, the ASCE and the Library of Congress to document historic sites and structures related to engineering and industry. Subsequently, this agreement was ratified by four other engineering societies. The Library of Congress website states that: “the collections document achievements in architecture, engineering, and design in the United States and its territories through a comprehensive range of building types and engineering technologies.” The HAER affirms that: “More than 50 years after its building, the Tunkhannock Viaduct still merits the title of largest concrete bridge in America, if not the world.”

The Nicholson Bridge was part of a larger project, called the Clarks Summit-Hallstead Cutoff, built to shorten the DL&W main rail line from Scranton, Pennsylvania to Binghamton, New York by 3.6 miles, lessen the steep grades that had previously required pusher engines, and straighten the rail line. The DL&W president at the time, William H. Truesdale, was looking for ways to modernize the railroad and make it more efficient. Not only did the railroad construct a smaller version of the Tunkhannock Viaduct nine miles north in Kingsley, Pennsylvania, called the Martin’s Creek Viaduct, the DL&W also built a 3,630 foot tunnel about two rail miles south of Nicholson. The entire cutoff, sometimes referred to as the Nicholson Cutoff, was built with two sets of tracks to allow for trains going north and trains going south at the same time. This shortened route costing $14 million saved considerable travel time between the two major cities: as much as an hour for freight trains and at least ten minutes for passenger trains.

At the turn of the 20th Century, the Lackawanna Valley, which included Scranton, was the industrial hub of Northeastern Pennsylvania. The Lackawanna Heritage Valley Authority website details the importance of the region’s coal, iron and steel industries: “Settled in the early 1800s, the rugged frontier (Lackawanna) valley rapidly grew to be a hub of commerce and manufacturing because of the enormous anthracite coal reserves just below the surface. The Pennsylvania Anthracite Region eventually produced 80 percent of the world’s anthracite coal, a clean, hot-burning fuel that was perfect for running machines and building empires. Historians consider Scranton the industrial center of the region. The huge coal industry, iron and steel production, railroading and railroad building, food processing, large-scale fabrication, and textiles all played a significant role in the area’s growth. The region became the powerful engine that drove America’s Industrial Revolution.” The Nicholson Bridge provided the capacity for increased goods, including coal, iron, and steel, and passenger traffic in the Northeast that contributed to the Industrial Revolution in the United States.